‘Exams’ Category

-

Language and The Handmaid’s Tale

11/09/2023 by axonite

Category Advertising, Exams | Tags: advertising,Language,Politics | No Comments

-

Getting into the Zone (Exam Prep)

16/03/2020 by axonite

For those of you with exams coming up, here is some advice. For those who don’t have exams, read anyway – it may well be of use later.

It’s not all about knowing the texts and demonstrating your command of the English language. What about you as a person? It’s natural to feel nervous before an exam. Use that energy. Channel it into your revision and exam practice, but don’t let nerves get the better of you. In the exam, breathe in slowly through your nose, hold for a moment, then breath out slowly through your mouth – you will find yourself becoming calmer.

Ensure that you get a good night’s sleep the night before the exam.

Use the toilet before the exam, but don’t feel embarrassed about asking to use the loo during the exam – it’s better to concentrate on your answers than on your bladder.

Make your table your world. Ignore everyone and everything else in the room – nothing else matters. Put your watch on the table and ignore the clock on the wall.

Ensure that you have two pens (at least) in the exam hall. There are always some students who have pens that run out of ink (and some even forget to bring pens with them!).

Start with whatever section gives you the possibility of the most marks (You can always rearrange the order of your papers at the end). Give yourself at least five minutes at the end to proof-read what you’ve written – you wrote fast under pressure, so there will inevitably be mistakes.

Don’t think that you can fob the examiner off with waffle. Here’s a genuine Year 11 essay:

This poem written by … is a poem that gives the reader a thought of the poem. As the reader reads the poem, he/she would get an image of the poem. The reader would be able to imagine a picture of what is going on in the poem. The choice of words that the poet uses makes it easier for the reader to get an image of the poem.

This bland, fault-ridden opening tells us nothing. One could apply it to any poem or prose excerpt that one has never bothered to read. No examiner will ever be fooled by this nonsense. It is waffle that the student hopes will disguise the fact that he/she does not understand the piece. Do not waste time writing this rubbish – instead, make meaningful and specific comments about the piece.

Now compare it to this response from the same class about the same poem:…is a romantic piece about two estranged lovers who live in different places.

Don’t rely on the teacher or think to blame everything on him/her. Even before the Internet, students were expected to demonstrate initiative and do their research in the library. Today, you have a wealth of information at the touch of a button. Use it – and don’t be tempted to make excuses. If something is unclear, don’t wait until the lesson. If you have a problem with your written expression – fix it (You will find many useful links on this very site).

Remember that you are students of Language primarily – in a sense, there is no such thing as a student of Literature – because it’s all about the words and their construction! With this in mind, don’t shy away from the poetry in the unseen exam – because you should be writing about pace, fluency, pitch and other such devices even when writing about prose.

Take the time to explore the texts and the language exercises to discover what you think. Don’t just blindly repeat what your teacher has said. CIE say:“Examiners can easily differentiate between students who have genuinely responded to literature for themselves and those who have merely parroted dictated or packaged notes.”

Smell is a great aid to memory (apparently). Try wearing the same perfume/aftershave on the day of the exam that you use when revising.

Timing! Plan your time properly. Start by answering the questions that have the potential to give you the greatest numerical score. Allocate your time appropriately. Read the questions three times to ensure that you understand – but don’t ever waste time on first drafts! Try to finish at least five minutes before the end of the exam – spend the last few minutes proof-reading – you can pick up valuable extra points this way.

Practise! Practise! Practise!

Here are the funniest (and most alarming) mistakes from previous exams. Enjoy.

“strucked…striked…hitted…builted…digged out”

“…about how they survived this disaster and geologists.”

“The earthquake was informed.”

“The speaker reveals everything that happens, using words.”

“Seamus uses some words to depict the mood and foreshadowing and metaphors.”

[n.b If you do not understand the words illustrate, depict and foreground, it is probably best not to use them]

Next, we have those who waste time with the blindingly obvious or the completely vague:

“The Mid-term Break is either ironic and not ironic.”

“Heaney expresses his feelings through various techniques.”

“The poet uses the word ‘angry’ to show that the mother is angry.”And finally, we have the Just Plain Weird category:

“Geogolists”

“The message will be sent forth” (Presumably with Moses from Mt Sinai)

“lossness”

“The destruction was handmade”

“…a warning to warn.”

“The poet instigate alliteration and assonance to emphasize the stopping of blood and life.”

“This past member is dead with bloods.”

“An illustration of a picture or the creation of imagery was extrapolate in the concluding stanza of the poem.”

“Seamus wants the conveys.”

“Seamus ironicly twisted both the tone and mood of his poem.”

“This poem consists of irony, sad mood and tone, and symbolism.”

“He was alone with his brother and many literary terms.”

“The person is Death.”

“emotional feelings”

“Heaney adds assonance and alliteration.”Just relax, do your best and don’t panic

Good luck

Exam Skills (University of New South Wales)

Category Exams, IGCSE, Study Skills | Tags: exams,IB,igcse,study skills | No Comments

-

Feedback on today’s past exam practice paper: Follower

16/03/2020 by axonite

Firstly (and most importantly) answer the question. You have been told repeatedly to do this – and yet the majority are still in the habit of ignoring it! It is not rocket science. In fact, it is the same the question every time! It will always ask you “how” a writer achieves his/her effects. It will not ask you to explain what the words mean. You must talk about techniques.

Take one technique for each topic paragraph. Extrapolate upon it. State clearly what/how/why.

There are no extra points available for writing about things that are irrelevant. Only answer the question.

Stop using the word “vivid” (even if it appears in the question). It does not mean the same as ‘descriptive’ nor ‘evocative.’

Look at the title. First think of the literal meaning before thinking of any possible figurative application and possible implications. Here, the title “Follower” literally means someone who walks about following someone else. It also suggests one who wishes to emulate and/or venerates another. It may even suggest a disciple.

As you read the poem it should become quickly apparent that the words demonstrate just this sense encapsulated in the title – that the son ‘followed’ his father. He expresses how, as a clumsy small child, he idolised his father (both literally around the farm and figuratively as his most ardent fan). The father is described as “an expert” who worked with skill (“mapping the furrow exactly”) and verve (“…with a single pluck”). He was a powerful giant of a man whose strength was seemingly that of Atlas (“His shoulders globed…”), whereas the child felt inept (“I stumbled…a nuisance…yapping…”). Heaney contrasts the two to communicate the shame and inferiority that he felt at the time. However, now, with the passing of years, an ironic reversal has occurred – now, as a famous poet, Heaney finds that it is his father who ‘follows’ him. The last two lines seem very harsh as Heaney says that his father is the one who ‘stumbles’ (presumably making mistakes and possibly being the embarrassment now) and “will not go away.” The venerated and the follower have switched places – but Heaney (the ‘voice’ of the poem not necessarily being exactly the same as the poet himself) appears to accept the situation with far less grace than his father before him.Category Exams, IGCSE, Poetry, Study Skills | Tags: exams,igcse,poetry,unseen | No Comments

-

Feedback on the recent Romeo & Juliet exam practice

11/03/2020 by axonite

The vast majority of people chose the first question. Here, most concentrated on explaining the meaning and implications of the imagery though – rather than on addressing the question of “in what ways does Shakespeare make you sympathise with Romeo and Juliet here?” Adapting your knowledge to the exact requirements of the question is a vital skill that you will need to practise.

In this particular question, the temptation to explain meanings should be resisted! (in fact, you will never be asked what – only how). There is so much content that could demonstrate your understanding – but if it is irrelevant, then it does not belong in your essay. This is very annoying when it happens, but you need to prepare for just such an eventuality. Here, in this question, it is only the emotional effect that interests us. There is no need to explain in detail in this response what birds or pomegranates signify – because what is important is that each element represents separation. Night and Day, the birds of night and day, the reference to Persephone, the sun and moon, life and death are all opposites – because the lovers are being pulled in opposite directions! They are torn between their desires and the demands of reality. The main way in which Shakespeare “makes us feel sympathy/creates a sense of” invites sympathy for the eponymous lovers is through the rich language. Yes, it is performed on stage (a visual medium) but it is not a movie – much of the visualisation arises from the words that Shakespeare has the lovers speak. It is hyperbolic. To modern ears, this exaggeration may seem silly, but it was intended to create emotional intensity.

The comical moments add piquancy to the lovers’ piteous parting, as they switch roles when Juliet realises the implications of Romeo staying any longer – her kinsmen will murder him. The notion of the lark “straining harsh discords and unpleasing sharps” is also amusing, undercutting the seriousness of their imminent separation. Thus, Shakespeare has Juliet declaim that (usually) “the lark makes sweet division” between night and day – but not now because it heralds the morning and Romeo’s hasty flight.

What of the rest of the extract? From the entrance of the Nurse, there is an even greater urgency, and they exchange intimate, highly relatable, tender assurances of love (I must hear from thee every day in the hour”). During their hurried terms of endearment, Juliet questions if they will “ever meet again.” Despite Romeo’s assurance that they will laugh about this in their future life today, the foreknowledge of their doom (from the chorus at the outset) ensures that this is a particularly poignant parting.

Question 2 is the general one. Here, we need to reflect on the ways in which Juliet and the Nurse interact over the course of the play. It is comical that this rambunctious and earthy woman (with her ribald humour) should be the surrogate mother for a highborn lady! As Friar Lawrence is confidant to Romeo, so the Nurse is to Juliet. When first we meet the Nurse, she talks of how she was originally a wet nurse to the baby Juliet (after her own daughter died). She speaks fondly of how Juliet “wast the prettiest babe that e’er I nursed” (that ever I nursed) indicating that there had been others. She also talks of how she dreams of one day seeing Juliet married. When Juliet confides her love for Romeo, it is the Nurse who acts as go-between. Although her duty is to Lady Capulet, her devotion to the daughter overrules her sense of decorum. Moreover, when Juliet is eager for the latest news of Romeo, the Nurse teases her by withholding the information, complaining about her aching feet and how she is out of breath. Juliet is exasperated, but quickly pleads with (and manipulates) the Nurse. This is more like the joshing of friends (a counterpoint to Romeo and Mercutio). However, ultimately the Nurse’s sense of pragmatism (in her advice to marry Paris and forget Romeo) leads to Juliet rejecting her. At the close of the play, whether or not the Nurse was truly a “good friend” to Juliet is thus a matter for personal judgement.Category Drama, Exams, IGCSE | Tags: drama,exams. IGCSE | No Comments

-

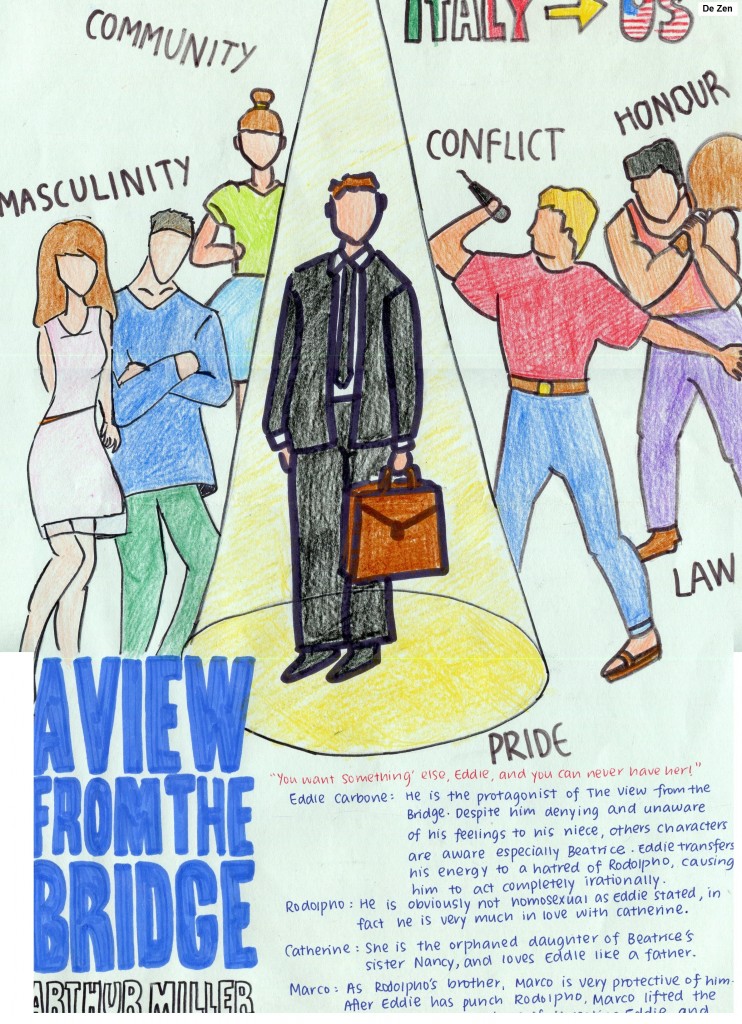

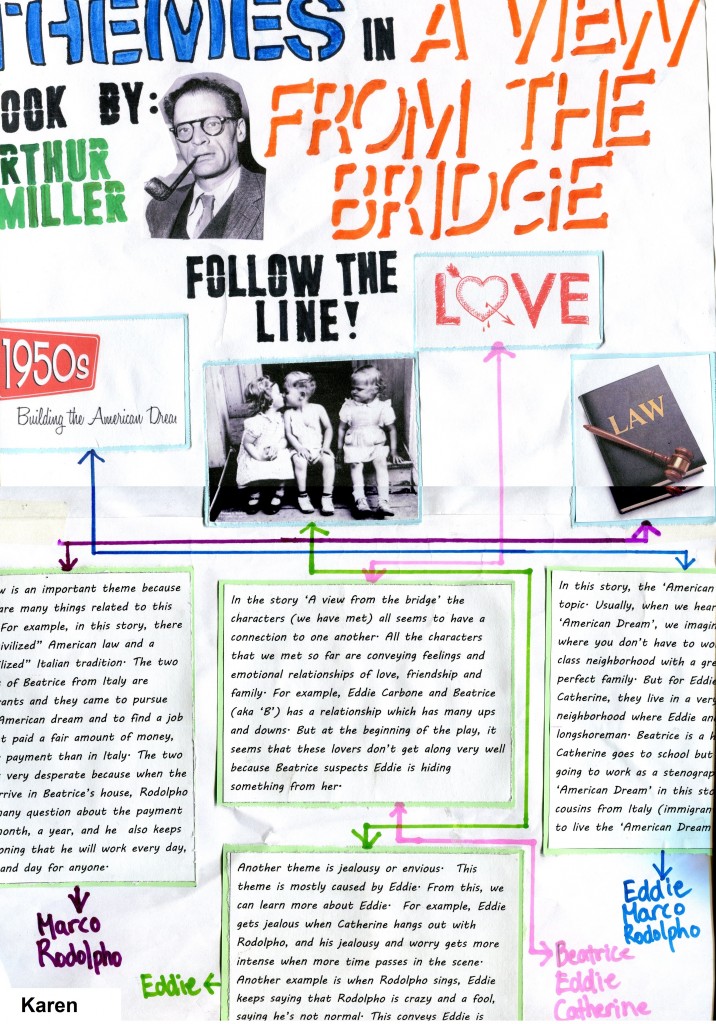

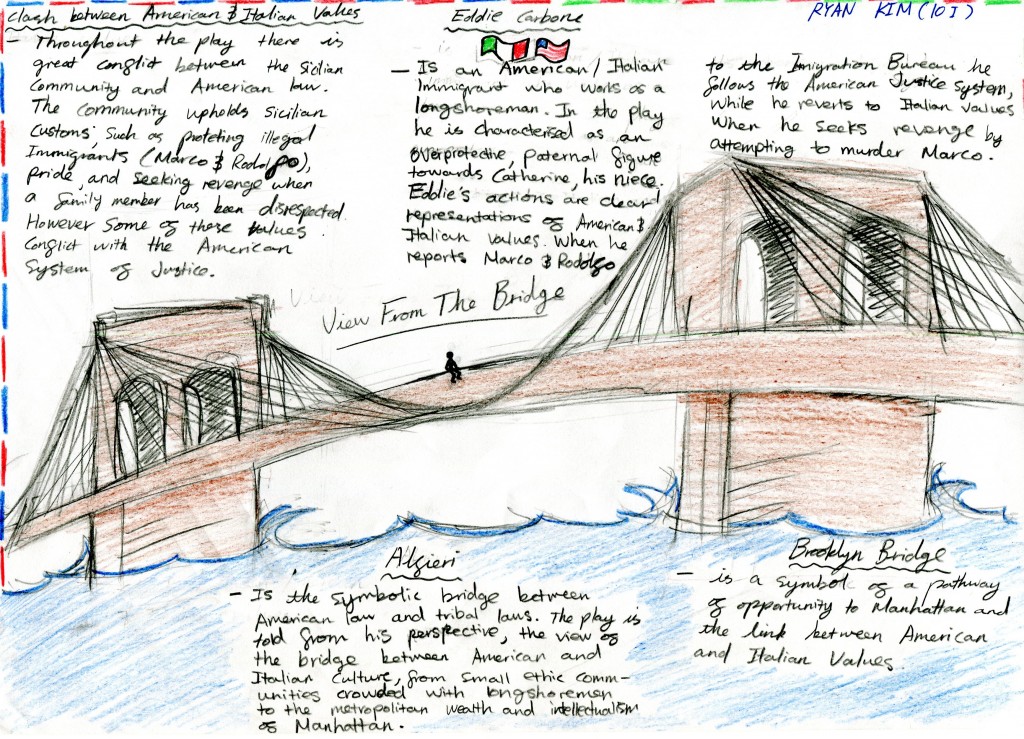

A View from the Bridge

16/03/2017 by axonite

Eddie, the tragic hero

Tragedies traditionally took as their heroes men and women of high office (kings, queens, princesses etc) but Miller believed the “ordinary” man to be an appropriate protagonist for his plays. In fact, he shows us characters who are not “ordinary,” an implicit statement that there is no such thing as “ordinary.” The USA is a meritocracy (at least in theory) where the power lies with the so-called “ordinary” person (again, at least in theory). Eddie is in fact from a solidly working class environment – but his passions are just as “Greek” (as Miller terms them) as any high-born emperor. Like them, his fatal flaw drives him to his own self-destruction. “Eddie Carbone had never expected to have a destiny.” A “destiny”? What does Miller mean by this?Eddie’s self-denial

Eddie cannot face up to the reality that he finds Catherine (his neice and god-daughter) attractive, and so he decides that “something aint right” about Rodolpho, the man she admires. His apparently effeminate attributes (and even his stature) seem evidence enough to Eddie that he is actually a homosexual and thus only interested in Catherine as a means to gaining American citizenship – the fact that he is buying luxury items seems to confirm this – “he’s here to stay,” Eddie says.Alfieri

Like Rod serling in The Twilight Zone, Alfieri acts as the narrator. His function is, in a sense, the “bridge” of the title – he acts as a link between our world (comfortable ‘tame’ middle class) and that of the working class American Italians in their enclave. The “bridge” is not just the literal Brooklyn one (from which we may look down as we pass over) but a functional one within the play itself.

Something’s lost, but something’s gained

Perhaps “civilised” means ‘tamed’? Yes, it means that there is less bloodshed (no more Al Capone), but is something lost too? Miller has Alfieri call Capone “the greatest Carthaginian of them all” – a man born in New York, not North Africa! Why? Probably because Carthage fought against the rule of Rome, which Miller may be using here as a metaphor for a civilising power. Southern Italians, in particular, have long held a deep suspicion of the law – but Alfieri notes that he now feels safer. Nevertheless, this “ordinary” man sometimes yearns for an idealised past on the Mediterranean. He feels a sense of loss. Something is missing now, something raw and vital. Something Authentic. Something that Alfieri admires in Eddie. Could it be that like Carthage, Eddie too wages an unwinnable war against a younger power? He is ultimately doomed (his “destiny”) but his refusal to back down, his insistence on regaining his “name” (his honour), is an admirable quality.Poetic Justice

Eddie dies from the very weapon with which he threatens Marco.

This scenario is often a cliche in action movies because it clears the hero of any blame – the villain is a victim of his own evil machinations (Typically, he forgets a trap that he set earlier or…he dies from his own hand in a duel). If the universe itself is somehow responsible for the villain’s doom, it is called Natural Justice. When the punishment fits the crime, we call it Poetic Justice. Is Eddie a villain? Is the universe punishing him? Does he (and remember that ‘he’ is a fictional construct representing people like ‘him’ in the real world) deserve his fate?“…something perversely pure calls to me from his memory…he allowed himself to be wholly known…I think I will love him more than all my sensible clients.”

Links

BBC Bitesize

Universal Teacher

Tragedy and the Common Man by Arthur Miller

The Arthur Miller SocietyCategory Drama, Exams, IGCSE | Tags: drama,exams,igcse | No Comments

-

Tackling the ‘Unseen’ poem

14/03/2017 by axonite

Poetry often seems to scare people. Here’s a straightforward video presentation that demystifies and helps you to understand and appreciate poetry:

n.b. The definition of alliteration in the video above is wrong – alliteration is the repetition of the initial (first) sound in a string of words. If those repeated sounds happen to be consonants, then it is also consonance – but if they’re vowels, it is also assonance.

Don’t forget that poetry is a different country (They do things differently there). Where you may think about a prose or drama excerpt, the poem is more for feeling. One good way of approaching a poem is to ask yourself how it makes you feel. This may or may not be the poet’s intention, but that’s beside the point – try to work out why it makes you feel this way. Then just ensure that you remove personal pronouns and focus it instead on the poet and his/her writing techniques (Always WHAT, HOW and above all WHY). Thus, “I feel uneasy when I read this poem” becomes “This poem generates a sense of unease through…” Finally, don’t forget that it is no good just to identify the ‘WHAT’ – you have to explain the HOW and the WHY.

Category Exams, IGCSE, Poetry | Tags: exams,IB,igcse,poetry | No Comments

-

Connecting content and form

28/10/2016 by axonite

The Lost Albums Loved by the Stars

The write-up for the first album cited here is a very good example of how to connect form and content in poetry. This is specific and focused, a far cry from empty claims or vague references that sometimes occur in poetry essays for IGCSE and IB. Take note.

P.S. Don’t forget that these are also the kinds of comments that you should be writing about prose too – it’s not just poetry that has rhythm, repetition and so on.

Category Exams, IGCSE, Poetry, Prose, Writing | Tags: exams,IB,igcse,Language,poetry,prose,writing | No Comments

-

Reservist by Boey Kim Cheng

30/09/2016 by axonite

In Reservist, Boey Kim Cheng regards the military service as laughable. He mocks it as being delusional (This is most evident in his reference to Don Quixote – “…tilt at windmills”). These are old men he says (“With creaking bones…grunts”) play-acting at being “knights” in some medieval farce – but the most that they can muster these days is being “battle-weary” ones before they even begin. They all look ridiculous (“…rusty armour…pot bellies”). Their “cavalier days” (when they looked dashing and vital in uniform) are long gone. Now they are a parody of a fighting force. It is pure “fantasy land” to expect these old and out of condition men to prepare for war. Moreover, Cheng appears to say that it is all for the vanity of those in power (“…kings’ command”) that they enact this pointless ritual (“We…Sisyphus”).

Category Exams, IGCSE, Poetry | Tags: exams,igcse,poems,poetry | No Comments

-

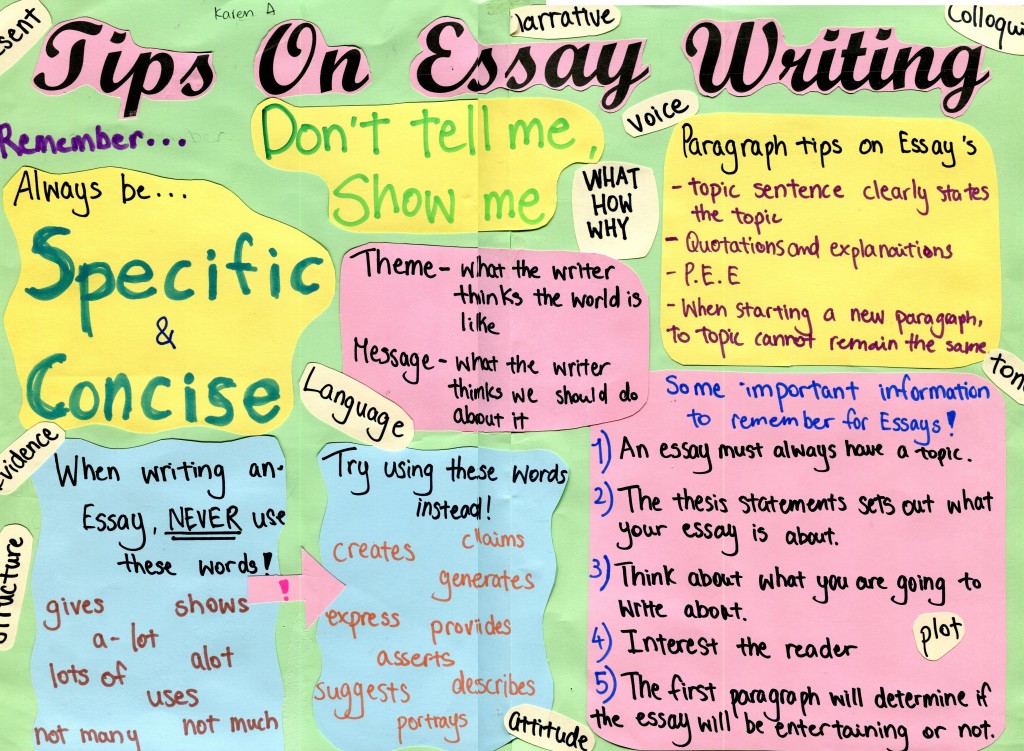

Essay Advice

16/06/2016 by axonite

Category Exams, IGCSE, Writing | Tags: commentary,exams,igcse,writing | No Comments

-

Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare

13/04/2016 by axonite

Greek words for ‘Love’

The Greek language has four words for “love”:

1. Agápe – undeserved love. In Latin, it is c(h)aritas. As English has the verb “cherish” from this Latin noun, the correct noun in English would be ‘cherishing.’ It is unselfish love as taught by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount and summed up by St. Paul the Apostle in 1 Corinthians 13.

2. Philía or the love between friends.

3. Storgé or familial love, especially between parents and their children and also with close relatives.

4. Éros, which has a pagan sexual sense, a Platonic philosophical sense and a religious sense. The basic meaning is attraction. It is also used for a person being ‘pulled’ towards God.

Sonnet 116 (The Marriage of True Minds) is a declaration, an idealistic manifesto. “Love,” as Shakespeare defines it, is not some shallow self-serving physical attraction, a James Bond style seduction that is really only about bolstering one’s own ego, but rather a “marriage of true minds.” It is reliable and constant (“an ever-fixed mark”) rather than an ephemeral fancy that fades with the beloved’s looks or youthfulness. Thus, it is clear that he is not talking of ‘romantic’ love or physical attraction at all – as the term “of true minds” implies, this is a wider and more lofty ‘love’ that is irrespective of gender or appearances. It encompasses friends (perhaps more so than lovers). It survives arguments and trying times (“looks on tempests and is never shaken”). Shakespeare is so certain of his belief that he states that if he is proved wrong, then he “never writ, nor no man ever lov’d.”

No, it’s not this.

…and certainly not this either.

It’s more like this.

…and this.

These couples will remind you what love is really about

Couple married for 64 years die holding hands, just hours apart

…and these:

Category Exams, IGCSE, Poetry | Tags: igcse,love,poetry,shakespeare,sonnets | No Comments