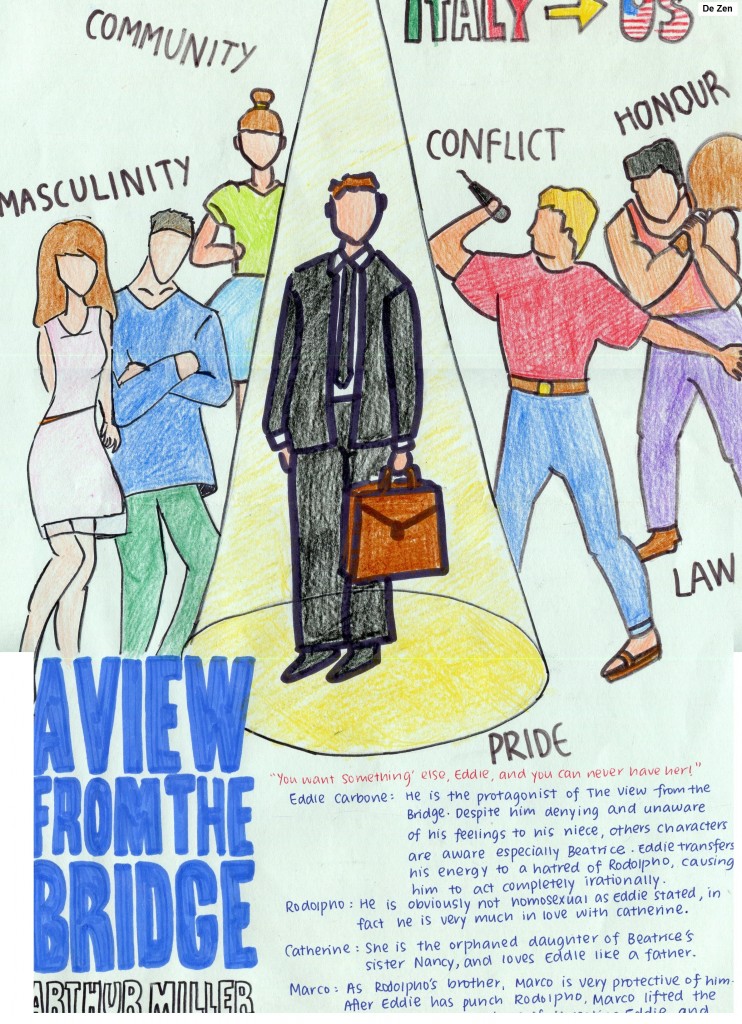

Eddie, the tragic hero

Tragedies traditionally took as their heroes men and women of high office (kings, queens, princesses etc) but Miller believed the “ordinary” man to be an appropriate protagonist for his plays. In fact, he shows us characters who are not “ordinary,” an implicit statement that there is no such thing as “ordinary.” The USA is a meritocracy (at least in theory) where the power lies with the so-called “ordinary” person (again, at least in theory). Eddie is in fact from a solidly working class environment – but his passions are just as “Greek” (as Miller terms them) as any high-born emperor. Like them, his fatal flaw drives him to his own self-destruction. “Eddie Carbone had never expected to have a destiny.” A “destiny”? What does Miller mean by this?

Eddie’s self-denial

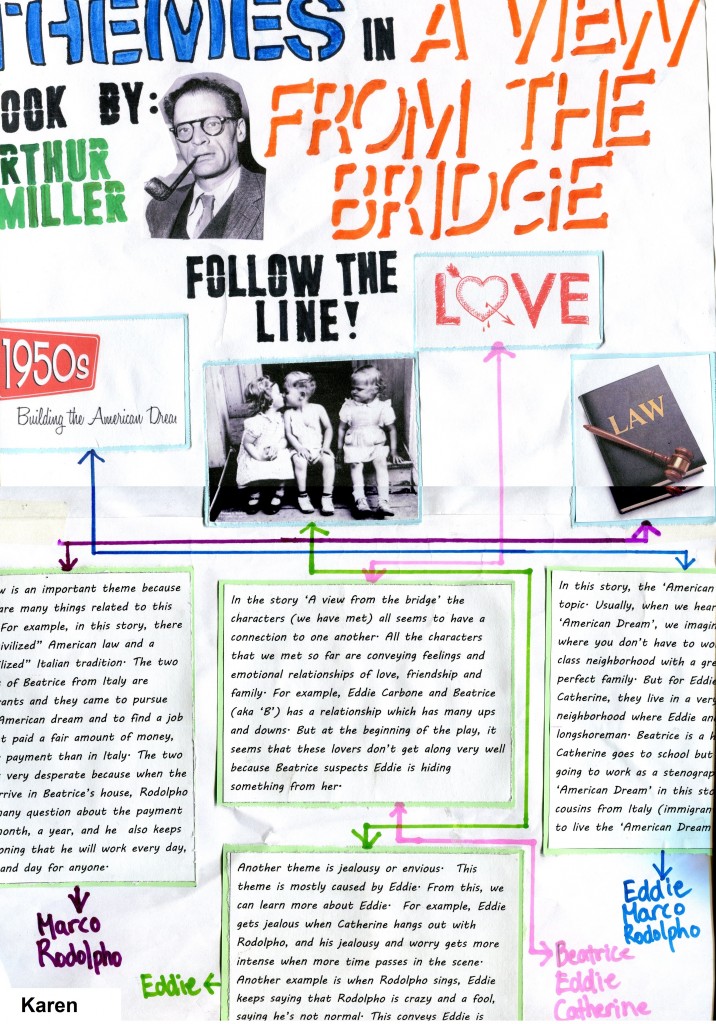

Eddie cannot face up to the reality that he finds Catherine (his neice and god-daughter) attractive, and so he decides that “something aint right” about Rodolpho, the man she admires. His apparently effeminate attributes (and even his stature) seem evidence enough to Eddie that he is actually a homosexual and thus only interested in Catherine as a means to gaining American citizenship – the fact that he is buying luxury items seems to confirm this – “he’s here to stay,” Eddie says.

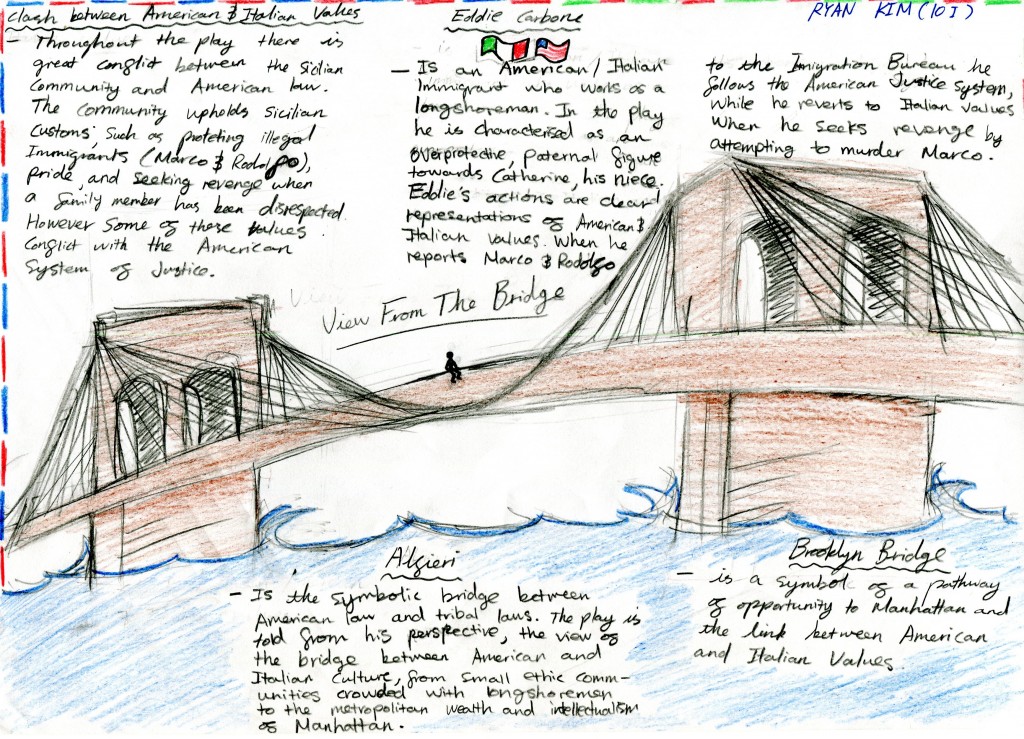

Alfieri

Like Rod serling in The Twilight Zone, Alfieri acts as the narrator. His function is, in a sense, the “bridge” of the title – he acts as a link between our world (comfortable ‘tame’ middle class) and that of the working class American Italians in their enclave. The “bridge” is not just the literal Brooklyn one (from which we may look down as we pass over) but a functional one within the play itself.

Something’s lost, but something’s gained

Perhaps “civilised” means ‘tamed’? Yes, it means that there is less bloodshed (no more Al Capone), but is something lost too? Miller has Alfieri call Capone “the greatest Carthaginian of them all” – a man born in New York, not North Africa! Why? Probably because Carthage fought against the rule of Rome, which Miller may be using here as a metaphor for a civilising power. Southern Italians, in particular, have long held a deep suspicion of the law – but Alfieri notes that he now feels safer. Nevertheless, this “ordinary” man sometimes yearns for an idealised past on the Mediterranean. He feels a sense of loss. Something is missing now, something raw and vital. Something Authentic. Something that Alfieri admires in Eddie. Could it be that like Carthage, Eddie too wages an unwinnable war against a younger power? He is ultimately doomed (his “destiny”) but his refusal to back down, his insistence on regaining his “name” (his honour), is an admirable quality.

Poetic Justice

Eddie dies from the very weapon with which he threatens Marco.

This scenario is often a cliche in action movies because it clears the hero of any blame – the villain is a victim of his own evil machinations (Typically, he forgets a trap that he set earlier or…he dies from his own hand in a duel). If the universe itself is somehow responsible for the villain’s doom, it is called Natural Justice. When the punishment fits the crime, we call it Poetic Justice. Is Eddie a villain? Is the universe punishing him? Does he (and remember that ‘he’ is a fictional construct representing people like ‘him’ in the real world) deserve his fate?

“…something perversely pure calls to me from his memory…he allowed himself to be wholly known…I think I will love him more than all my sensible clients.”