Now is always the perfect time to chill out with a good book.

“Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read.”

— Groucho Marx

“So please, oh PLEASE, we beg, we pray, Go throw your TV set away, And in its place you can install, A lovely bookshelf on the wall.”

— Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

“There is more treasure in books than in all the pirate’s loot on Treasure Island.”

— Walt Disney

Best Sci-Fi Authors

01 Isaac Asimov

02 Arthur C Clarke

03 John Wyndham

04 John Christopher

05 Ray Bradbury

06 H.G. Wells

07 Alan Dean Foster

08 Orson Scott Card

09 Brian Aldiss

10 Jack Chalker

11 Theodore Cogswell

12 Theodore Sturgeon

13 Harry Harrison

14 Jack Williamson

15 William Nolan

16 Harlan Ellison

17 James Blish

18 Jack Vance

19 Fritz Leiber

20 Bob Shaw

Best Fantasy Authors

01 J.R.R. Tolkien

02 Terry Brooks

03 Steven Erikson

04 Alan Dean Foster

05 George R.R. Martin

06 Ursula K. Le Guin

07 Robin Hobb

08 Roger Zelazny

09 Terry Pratchett

10 David Eddings

11 Frank Herbert

12 Raymond E. Feist

13 T.H. White

14 Robert Jordan

15 David Gemmell

16 Stephen R. Lawhead

17 Mervyn Peake

18 Jack Vance

19 H.P Lovecraft

20 Philip Jose Farmer

Best Comedy Authors

01 P.G. Wodehouse

02 Bill Bryson

03 Harry Harrison

04 Terry Pratchett

05 Jerome K. Jerome

06 Kingsley Amis

07 Tony Hawks

08 Stella Gibbons

09 Evelyn Waugh

10 Douglas Adams

11 Joseph Heller

12 James Herriott

13 Isaac Bashevis Singer

14 Malcolm Bradbury

15 Grant Naylor

16 Bob Shaw

17 J.K. Rowling

18 Spike Milligan

19 Sue Townsend

20 Gerald Durrell

Best Crime Authors

01 Arthur Conan Doyle

02 Agatha Christie

03 Stieg Larsson

04 Raymond Chandler

05 Dashiell Hammett

06 Ruth Rendell

07 Henning Mankell

08 P.D. James

09 Dorothy L Sayers

10 Patricia Cornwell

11 James Patterson

12 Colin Dexter

13 Ellis Peters

14 Patricia Highsmith

15 Ed McBain

16 Harlan Coben

17 Ian Rankin

18 Ann Cleeves

19 Barbara Vine

20 Josephine Tey

Best Horror Authors

01 M.R. James

02 Stephen King

03 Bram Stoker

04 Mary Shelley

05 Jack Williamson

06 Richard Matheson

07 Edgar Allan Poe

08 H.P. Lovecraft

09 Ray Bradbury

10 Clive Barker

11 Robert Bloch

12 Algernon Blackwood

13 Ambrose Bierce

14 Dean Koontz

15 Clarke Aston Smith

16 James Herbert

17 Anne Rice

18 Peter Ackroyd

19 Charles Beaumont

20 Ira Levin

Best Modern Playwrights

01 Tom Stoppard

02 Arthur Miller

03 Brian Friel

04 Samuel Beckett

05 Bertolt Brecht

06 Caryl Churchill

07 Harold Pinter

08 George Bernard Shaw

09 Willy Russell

10 David Williamson

11 T.S. Eliot

12 David Mamet

13 Ariel Dorfman

14 Stephen Sondheim

15 Lucy Prebble

16 Wole Soyinka

17 Alan Bennett

18 Alan Ayckbourn

19 J. B. Priestley

20 Terence Rattigan

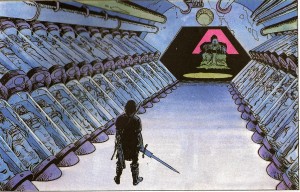

Best Graphic Novels

01 Charlie’s War

02 Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

03 V For Vendetta

04 Planet of the Apes: Cataclysm

05 Persepolis

06 Space 1999: To Everything That Was

07 Nausicaä

08 Thorgal

09 Galaxy Express 999

10 Dan Dare

11 Watchmen

12 Maus

13 Storm (Don Lawrence)

14 The Freedom Collective

15 2001 Nights of Space

16 Wulf, The Briton

17 The Vagabond of Limbo

18 Citizen of the Galaxy

19 Judge Dredd: The Cursed Earth

20 Strontium Dog

Links

The Big Read

The 100 Best Novels

Libraries that look like Alien Spaceships

Who killed Literature?

Ursula K. Le Guin Names the Books She Likes and Wants You to Read