“Thou art translated” – A Midsummer Night’s Dream (III. i. 112-13)

While Shakespeare’s play is clearly not about interlingual translation in any overt sense, there nevertheless is a respect in which it reflects the issue of what is involved in the translation from one language and cultural tradition to another, and most particularly the fact that such an activity inevitably entails a displacement and transformation as well as a potential deformation of its object.

Oxford Journals: Essays in Criticism

Because the Qur’an stresses its Arabic nature, Muslim scholars believe that any translation cannot be more than an approximate interpretation, intended only as a tool for the study and understanding of the original Arabic text.

Just Islam

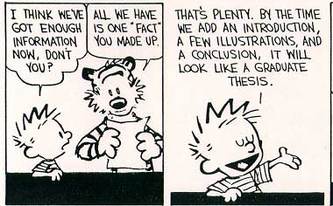

Do we mean what we say?

Language is an approximation of meaning, but as meanings change, so the language must too. However, for many people, particularly those from marginalised groups, language is an important expression of identity. To deprive a people of their own language and to impose another is a form of cultural imperialism. French was the legal language in England for 200 years, but while English survived, it emerged different, transformed – a reflection of new realities. However, some languages vanish without trace.

Why do we learn?

In Friel’s play Translations, the initially innocent-seeming translations of place names are gradually revealed to have more sinister implications – but he does not stop there. As many critics note, this is not a two-dimensional play. No matter what the rights and wrongs of displacing a language, many will wish to learn the oppressors’ tongue (Hence the Latin and Norman French roots of words that survive even today in English) for practical reasons. The language of poetry or of love may be replaced by the language of commerce – and this issue strikes deep, going far beyond words to values. Do we learn to edify alone or to fit ourselves with skills for the world? And if we only learn to acquire skills, are we then missing some essential part of our humanity? Those who study purely for edification become irrelevant, whereas those who study purely for skills become philistines.

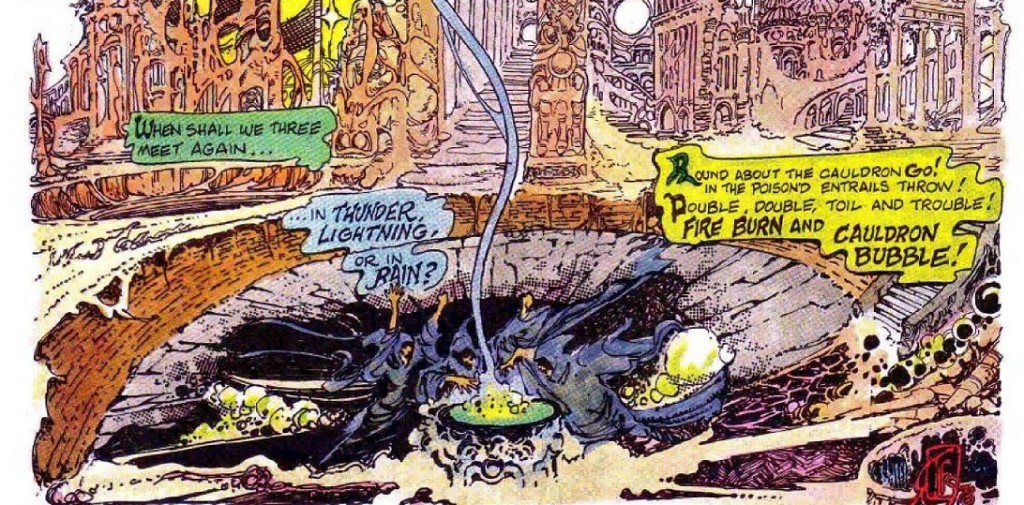

It’s a kind of magic!

My words when they speak me

Do we speak the words or do the words speak us? This is a question that has puzzled the brightest of minds (and which we will encounter again in other plays in this unit). Some claim that the concepts embedded within a language (and even the sounds of the words) shape our thoughts. Words have power over us, we are told. In its extreme form, we see in the Bible that Peter’s words condemn him – he denies three times that he knew Jesus (Matthew 26:72), then later must undo this curse that he has brought upon himself by saying three times that he loves Jesus (John 21:14).

Productions

Rose theatre, Kingston

Crucible, Sheffield

Syracuse University

Dying Languages

Intl Business Times

The Independent

BBC